By Uche J. Udenka

Some truths do not insult nations; they expose them.

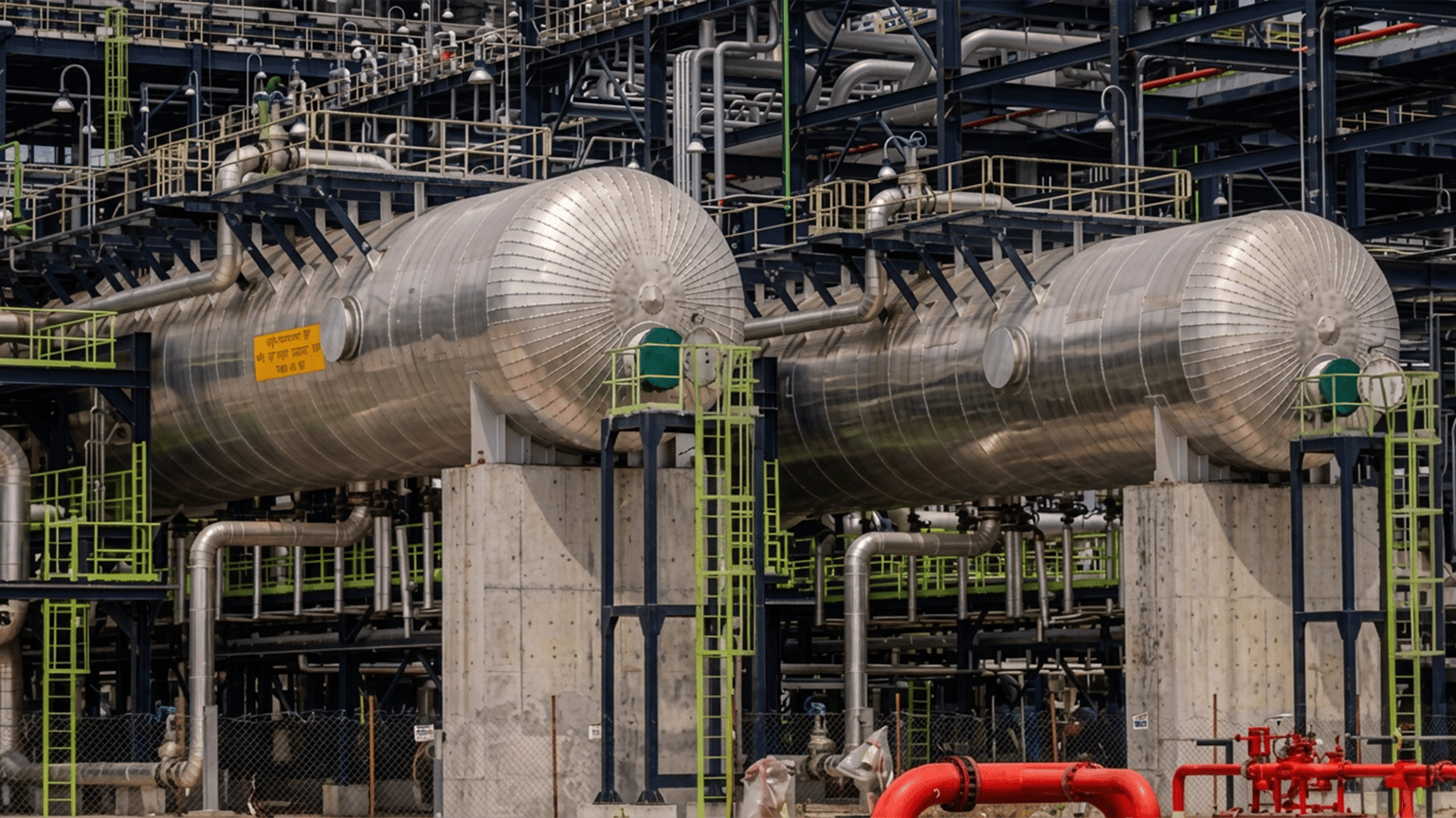

The controversy surrounding the recruitment of thousands of Indian technicians for the Dangote Refinery has triggered outrage across Nigeria. For many, it feels like an affront to national pride: how can Africa’s largest economy, with over 230 million people, fail to supply the manpower to run its most ambitious industrial project? But outrage, in this case, misses the point. What the Dangote episode reveals is not a scandal—it is a mirror. And mirrors do not lie. They simply show us what we have become. Nigeria’s problem is not Dangote’s preference—It is Nigeria’s preparation.

Dangote is accused of choosing foreigners over Nigerians. That accusation is emotionally satisfying but intellectually hollow. Capital does not run on sentiment. A refinery does not operate on patriotism. It runs on precision, competence, safety protocols, and deep technical knowledge.

The uncomfortable truth is this: If Nigeria had produced thousands of refinery-ready technicians, they would be employed already. Dangote’s choice is not ideological; it is operational. He did not recruit Indians because they are Indian. He recruited them because they know how to run refineries. That is not an indictment of Dangote. It is an indictment of our systems.

Africa was not defeated by guns—but by skills it refused to build.

Nigeria’s predicament is not unique. Ghana faces it. Kenya faces it. Senegal, Angola, Cameroon, and the DRC face it. Across Africa, modern infrastructure is rising—ports, power plants, refineries, railways—but the hands that build, configure, and maintain them are often foreign. We provide land, licences, tax holidays, and raw materials. Others provide skills. This is the silent continuity of dependency.

Africa did not lose its place in the world because it lacked intelligence or ambition. It lost ground because it neglected technical competence while others industrialised relentlessly. While we politicised education, others professionalised it. While we expanded universities without workshops, others expanded polytechnics with teeth.

Technical education: The graveyard of African neglect.

In Nigeria and Ghana alike, technical education has been treated as a second-class option—something for the “less brilliant,” the “non-academic,” the socially invisible. Our technical colleges are underfunded. Our curricula are outdated. Our workshops resemble museums of abandoned ambition. Our instructors are often unretrained for modern industry. Parents dream of lawyers, doctors, politicians, and professors.

Few dream of industrial mechanics, process technicians, welders, or control engineers—yet these are the people who keep modern civilisation alive. This cultural contempt for technical work is one of Africa’s most destructive inherited errors. The modern world does not run on theory alone. It runs on people who understand systems—electricity, oil, software, machines, logistics. And this is where Nigeria and Ghana are bleeding quietly.

Without skills, even wealth becomes dependent.

The Dangote Refinery is proof that money alone cannot compensate for weak human capital. Nigeria is rich in oil. Ghana is rich in gold and bauxite. Africa is rich in cobalt, lithium, gas, and arable land. Yet we remain dependent—not because we lack resources, but because we lack enough people trained to transform them. Ownership without capability is symbolic. Sovereignty without skills is incomplete. A country that cannot run its own machines does not fully control its destiny, no matter how many billionaires it produces.

This is not a Nigerian crisis—It is an African one.

What Nigeria is experiencing today is simply Africa confronting itself honestly. Across the continent: Power plants are maintained by foreigners

Mines are calibrated by foreigners. Data centres are configured by foreigners

Industrial plants are operated by foreigners. We inaugurate projects we cannot fix.

We celebrate infrastructure we cannot maintain.

Development has become ceremonial—ribbon cutting without operational mastery. Real development begins when foreign expertise becomes optional, not essential. The real revolution Africa needs is technical, not rhetorical. Africa does not need more slogans, summits, or glossy “Vision 2030” documents. It needs mass technical competence. Not a few hundred technicians a year. Not pilot programmes for donor reports.

Nigeria and Ghana need tens of thousands of well-trained technicians yearly—industrial electricians, refinery technicians, automation experts, welders, maintenance engineers, IT systems builders. This is how countries rise: not by talking about industrialisation, but by staffing it. Asia did not wait for perfect governance before building skills. It built skills first—and governance followed under pressure from productive citizens.

The Dangote lesson: A wake-up call, not an embarrassment.

The right question is not, “Why are Indians working there?” The right question is, “Why did our education systems fail to produce Nigerians and Ghanaians who could replace them?” This question indicts ministries of education, political elites, budget priorities, and societal values. Dangote did not humiliate Nigeria. He exposed a structural weakness we have long avoided confronting. And exposure, painful as it is, is the first step toward reform.

A continent cannot take off without knowing how its engine works. The 21st century will not be won by countries that shout the loudest about sovereignty, but by those that quietly build competence. As long as Nigeria and Ghana neglect technical education, they will remain markets—not manufacturing powers. As long as Africa consumes what it cannot produce or maintain, dependency will wear new clothes but remain dependency.

The day African cities begin graduating thousands of industry-ready technicians every year, the balance will shift. On that day, Africa will stop asking for respect. It will command it. The future belongs not to those who own resources, but to those who know how to transform them.

Udenka is a social and political analyst.

In this article