The court, they say, is a beacon of justice but the officials of Lagos courts do not align with the age-long dogma. In this report, BUSOLA ARO exposes the shady practices perpetrated by judicial officials who extort applicants and demand unofficial fees before issuing documents and certified true copy (CTC) of court rulings. From the federal high court in Ikoyi to the Agege magistrate court and the Ikeja high court — the pay-for-document racket was found to be prevalent and deemed to be normal.

When I arrived at the four-storey building housing Samuel Ilori magistrate court in Ikeja on a sunny afternoon in April 2022, the environment was busy and tense. Alleged criminals, security operatives, lawyers, relatives of alleged criminals, court officials and non-officials crowded the place.

Samuel Ilori court, Ogba I proceeded to Court 9 on the third floor and on arrival, I approached the court registrar and submitted an application requesting the CTC of a judgement. Begrudgingly, she collected the letter, took a look at it and directed me to the records department, saying all files had been transferred there.

The records office is on the first floor, so I navigated my way back down the stairs. There I met an official identified as Alhaja Khadijat, who patiently listened to my enquiries and directed me to the assistant chief registrar (ACR) where I would initiate my application.

“Why are you applying for this CTC?” the ACR asked when I approached her. “Are you related to the parties involved and what do you need it for?” After providing answers deemed satisfactory, she signed the document and referred me to the records officer.

ACR asking numerous questions

Upon my return, Khadijat was arranging files and attending to other persons. After some time, she turned to me and asked; “So, what can I do for you? You can see that I am busy. I don’t believe your file is here and you can also see that there are so many files here. So, you would have to come back before you can get it.

ACR asking numerous questions

Upon my return, Khadijat was arranging files and attending to other persons. After some time, she turned to me and asked; “So, what can I do for you? You can see that I am busy. I don’t believe your file is here and you can also see that there are so many files here. So, you would have to come back before you can get it.

“If you want to get the CTC today, you would have to mobilise people to help you look for it. I cannot leave what I am doing to look for your own when there are more important people who have come before you. You ought to know what to do. Those people won’t work for free unless you are ready to come back in two weeks.”

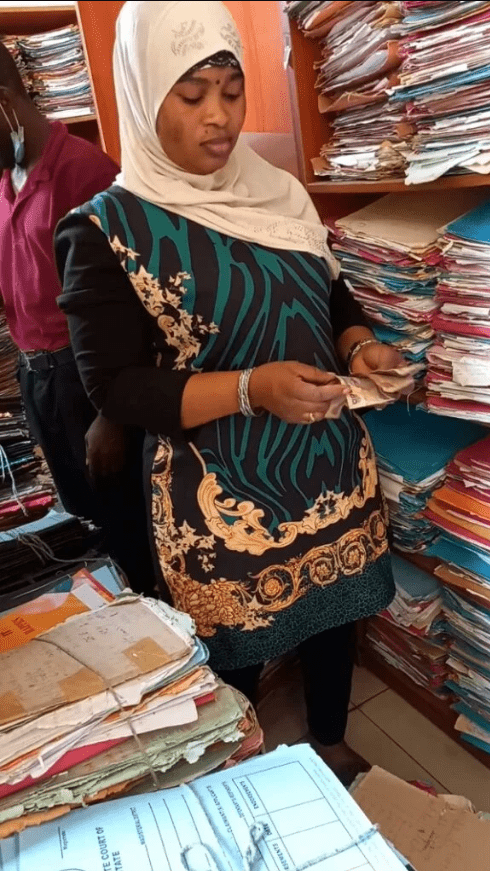

Khadijat counting the mobilisation fee

After receiving N2000 as a mobilisation fee, she asked me to return in two days. I returned four days after, but Khadijat had not yet treated my request, and she gave the impression that I would have to pay another sum to fast-track my work. I left and returned the following week but there was still no progress. Unwilling to cough out another sum, I gave up.

Khadijat counting the mobilisation fee

After receiving N2000 as a mobilisation fee, she asked me to return in two days. I returned four days after, but Khadijat had not yet treated my request, and she gave the impression that I would have to pay another sum to fast-track my work. I left and returned the following week but there was still no progress. Unwilling to cough out another sum, I gave up.

HOW TO APPLY FOR A CERTIFIED TRUE COPY

Applications for court documents such as the CTC is one of the major activities in Lagos courts. Lawyers, journalists and parties to cases request documents, especially the CTC, on a daily basis.

To get court documents, one is expected to write an application addressed to the registrar or deputy registrar, after which necessary validations such as payment and stamping are done. This process only takes an hour depending on the number of requests as cases are filed every day.

The procurement of a document has a set of procedures — starting from the deputy registrar who initiates the document to the specific court where the document is to be obtained; then you make a photocopy, visit the litigation officer who gives the official amount, then to the cashier to make payment, and back to the litigation office to get a certified stamp.

Cashier office and initiation room

To apply for a CTC in the federal high court, Lagos costs about N300 per page. In the state high court or magistrate courts, it costs N200 per page. But the rates are just the official amount on paper. Applicants are expected to cough out more to guarantee an expedited process. It’s essentially a game of ‘bargain, pay or get rebuffed’.

Cashier office and initiation room

To apply for a CTC in the federal high court, Lagos costs about N300 per page. In the state high court or magistrate courts, it costs N200 per page. But the rates are just the official amount on paper. Applicants are expected to cough out more to guarantee an expedited process. It’s essentially a game of ‘bargain, pay or get rebuffed’.

THE JUDICIARY AND ITS NEW NORMAL

At the federal high court, Ikoyi, the administrative building is separated from the court building, I met a somewhat friendly woman who collected the letter and went to an inner officer for a few minutes. When she returned with the letter, “Mr Charles, please treat” was written on it.

Mr Charles is in charge of litigation and case files. “Go to the judge’s court and collect the judgment,” he told me when I approached him. At the court, the official on duty glanced at me fleetingly, and asked nonchalantly: “How much are you paying?”

“Nobody asked me to pay anything,” I told him.

“There is no judgment here,” he responded. I offered him N1,000 and he collected the letter. “You came from a newspaper company. You people are rich. Pay N20,000 or no judgment,” he insisted.

After pleading with him, and eventually bargaining, the middle-aged man collected N1,800 from me. As soon as I got the judgment, I headed back for Charles’ office, who, upon arrival, asked me to pay another N450 as the “court summons fee”. I obliged and went back to get the document stamped and presented my receipt.

But Charles made me understand that there was more payment to be made.

“I hope you know you are to pay N1,000,” he said. “Do you know that every single thing used for work in this office wasn’t bought by the government, or do you think it is? We have to supply them ourselves. So, you have to pay so that these things can be available.”

To buttress his point, he displayed the stamps, ink cartridges, and other items to me. I explained to him that I had spent quite some money to procure the document and as such, I wouldn’t be able to pay more money. After some bargaining, I conceded and parted with N500.

“If I tell you that I don’t have ink and you have to provide it, will that not be worse?” he added.

On my second visit to the court in Ikoyi, I met one Edwin and he directed me to Yusuf Olubodun, popularly called professor. The latter’s responsibility is to attend to applications. The court floor was littered with case files, yet Olubodun carefully and painstakingly searched for what I requested.

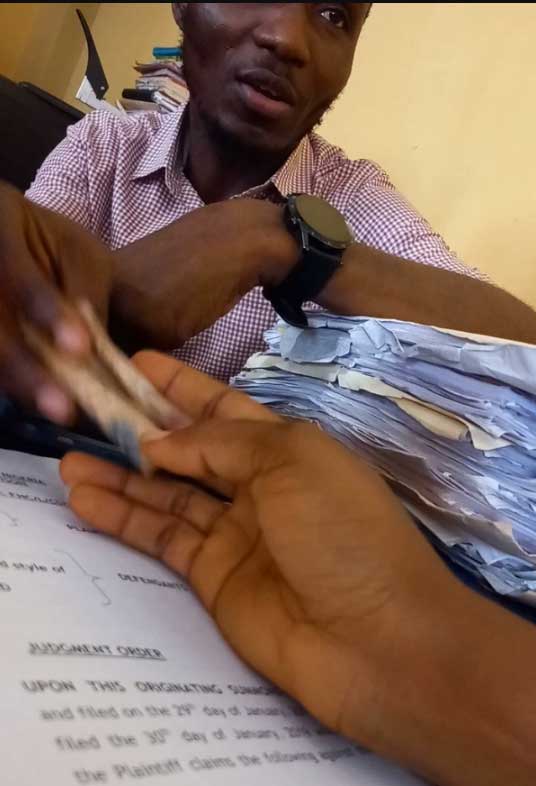

“I have searched for your document successfully but for me to release it, the document would cost you N20,000. You know I have been nice to you,” he said.

His colleague, Edwin, who was privy to the conversation, asked, “is she cooperating?” At that point, I knew I had to bargain. I did and eventually parted with N4,000.

Olubodun collected N4000 as the fee for the CTC.

After I made photocopies of the document, Olubodun and I went to see Joseph Agbo, the litigation officer who is also the principal executive officer. He signed and added the official charge to the document. Then, I made an online payment of N282. Afterwards, I went back to the cashier who rectified the payment and collected two copies of the payment receipt.

After I made photocopies of the document, Olubodun and I went to see Joseph Agbo, the litigation officer who is also the principal executive officer. He signed and added the official charge to the document. Then, I made an online payment of N282. Afterwards, I went back to the cashier who rectified the payment and collected two copies of the payment receipt.

EPE HIGH COURT

Epe high court You probably might be lucky as I was on March 30 when I visited Epe court, Lagos. After transiting for six hours, I arrived at the court panting and fatigued.

Unlike the previous experiences, procuring a CTC was a smooth process at Epe, and all the errors made were corrected by the registrar of Court 2. The registrar, identified as Samuel, patiently attended to me and ensured I left in due time.

Two pages of court proceedings only cost N400 while N200 was paid for a red stamp. The official process was followed to the letter.

N5,000 FOR HOSPITALITY AT IKEJA HIGH COURT

Upon arrival at the Ikeja high court, the registrar asked me to sit down, after which he collected my letter and asked an official named Seun to search for the document. Less than 10 minutes later, Seun returned with the document and then I was asked to pay N200 for the photocopy which I hurriedly did. Once the photocopy was done, I naively thought I would walk out with the document — but the registrar brought me back to reality. He told me the next step is to pay N5,000 for “hospitality”.

The registrar(seated) and Seun deliberating on the hospitality fee

I told him I didn’t have such an amount and I bargained for N2,000. “That’s too small for helping you retrieve the document with ease and for your information, we don’t release documents to people who are not parties to the case,” he said, despite the fact that there’s no law backing his claim.

The registrar(seated) and Seun deliberating on the hospitality fee

I told him I didn’t have such an amount and I bargained for N2,000. “That’s too small for helping you retrieve the document with ease and for your information, we don’t release documents to people who are not parties to the case,” he said, despite the fact that there’s no law backing his claim.

Eventually, we agreed on N3,000, which I paid immediately to have the documents processed. The cashier was fast enough to attend to me. The document was eventually stamped after paying another N1,600 for eight pages.

LAWYERS ARE NOT SPARED

Sola, a lawyer who has been practising for three years, described his experience at the cashier’s office of the Ikeja high court.

“I came to file a particular matter and all I filed for is just N300, but I had to settle them at the cashier stand with N500. Sometimes, I end up spending more than N1,200,” he said.

“Today’s process is better. And the process depends on how many people you would have to meet or offices to do one thing or the other. However, there are several alternatives.

“You can either negotiate with the court registrar or meet any court steward who would run the errand of getting the CTC, pay officially and get it stamped or you go through the process yourself. You can be sure of spending close to N10k to N15k.”

Ubani Monday, another lawyer, said he has been extorted at all the courts, describing the judiciary as “one of the fountains of corruption”.

“It is shocking how these registrars ask for money with the confidence that nothing can be done to them. They do it mostly, especially to lawyers,” he said.

“There was a time I wanted to compile records of proceedings and they asked me to bring N5 million. Some charge 20k to 30k for proof of service. For a case to be assigned to the court, you have to pay. Only the industrial court is clean.

“At every point, there is extortion. Execution of judgment is also paid for, sometimes above N500k.

“When justice is not served but paid for, corruption leads to denial of justice.”

ANY SOLUTION IN SIGHT?

Adedamola Olaotan, a human rights activist, said extortion and collection of bribes by court officials and the long process of obtaining CTC are as old as the judicial system of Lagos state.

He said poverty, greed, poor remuneration, lack of discipline among judicial personnel and the inability to digitise the judicial system are responsible for the rot.

“Another cause of the malaise is court congestion. Due to the commercial activities in Lagos state, litigants and their lawyers become desperate and adopt various means including offering financial inducement to the court officials to give priority to their cases,” Olaotan said.

“One of the ways of eradicating the malaise is to review the wages/salaries of judicial staff and give them a reorientation that extortion and bribery are not good for the image of the judiciary. Another, most effective way is for the judiciary to adopt online filing of documents. This will reduce the contact between the litigants, lawyers with the judicial staff.

“Lagos state so far is trying in this direction by coming up with the pre-action protocols for litigation. More still needs to be done.”

Olaotan expressed hope that the system will be cleansed with the introduction of technology and increased remuneration of judicial officials.

When contacted about the issues uncovered, Grace Alo, public relations officer of the Lagos ministry of justice, said the chief registrar of the state high court was in the best position to comment.

TheCable subsequently reached out to Elias Tajudeen, the chief registrar, via a letter dated July 5, 2022, but received no response despite several visits to his office.

This is a special investigative project by Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) in partnership with TheCable, supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Published materials are not views of the MacArthur Foundation.