By Dan Agbese

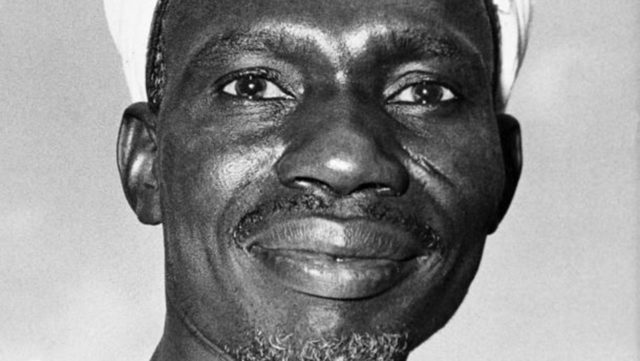

The late Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa.

Saturday, October 1, 1960. The Union Jack came down from the flag pole and yielded a permanent place to a new national flag – green-white-green. Nigeria became an independent, sovereign nation. Few things could be more momentous for a colonised country now set free. The Prime Minister, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, the golden voice of Africa, exulted: “Today is Independence Day. At last, our great day has arrived, and Nigeria is now indeed an independent sovereign nation.”

He made that statement fully conscious of the seductive promises of independence and the critical challenges of building a new nation on the foundation laid by the British. He certainly, had no illusions about what he faced as the leader of our new nation. Fate had thrust on his delicate shoulders enormous responsibilities that were somewhat made light by the infectious exhilaration of freedom. He knew that our challenges would not be a matter of magic and our problems would not be solved by mouthing abracadabra. He knew more than most people that what we made of our independence would either make it meaningful or meaningless. Our dreams would either be dreams or nightmares. It was ours to determine. His voice still rings through the midst of time.

There are not many of those who witnessed that day who are still alive today. Many of them lived long enough to witness the ups and downs that have characterised our movement as a nation and went into their graves with mixed feelings about where we were headed as a country. Two generations of Nigerians have sprung up since we replaced the Union Jack with our new national flag. But there is no Nigerian born long after October 1, 1960, who remains unaffected by the promises of independence 61 years ago. The critical and often elusive challenges of one nation forged from the unity of tribes and tongues are human challenges wrapped in dreams of everyone being the architect of a greater tomorrow. His voice still rings through the mist of time.

As I listened to his golden voice today through the mist of time, 61 years later, I began to wonder what the late prime minister would make of what we have made of our independence and its many promises and its many challenges. I do not think he would be happy with what he sees of our republic today. He would see that more things have gone wrong than right with our country since the gun became the instrument of political power and criminality. He would see that we are still members of our tribes first and citizens with some reluctance. He would see that we rose and we fell. He would see that we swing from the boughs of inconsistencies because we speak from both sides of the mouth in matters of national interest.

He would see that our banner is badly stained with the precious blood of our innocent citizens; he would see a fractious republic steadily sinking in the morass of our collective duplicity; he would see that tongues and tribes now differ so much that we find it impossible to stand in brotherhood; he would be confronted with the unsettling fact of our dangerous religious divide such that the division determines who gets what and who becomes what; our multi-religious nation is held hostage by religious irredentists who equate service to their faith with service to the nation.

The late prime minister would not fail to see that we have failed so far to beat the tribes and the tongues into hoes for our national development and that national unity and cohesion have been turned into so much hot air absent of patriotic commitment; he would see that we talk at one another; not with one another; he would see that what passes for our national conversations is a throaty yes or no delivered in extreme positions; he would see that our fault lines keep widening; he would see that our politicians continue to put self above the nation and have thus turned Nigeria into a nation of big men and not a nation of laws; he would wonder at our federal system that is neither truly federal nor truly unitary; he would see a flawed federal system different in every particular from both the independence and the republican constitutions, the latter midwifed by his own government to make the country live the true meaning of its independence from Britain.

And he would wonder. He would wonder how an oil-rich nation became the poverty capital of the world with 100 million of its citizens officially classified as extremely poor; he would wonder what happened to our agriculture that a nation with 80 per cent arable land became a net importer of food from countries with 30 per cent arable land; he would wonder at what point in its life the giant of Africa developed feet of clay and lost its acclaimed leadership of Africa and the black nations of the world.

He would be shocked to learn that whereas his government was toppled in a bloody coup in which he lost his life on the allegation of corruption by the young majors, corruption still reigns and has passed the pittance of ten per cent to the stratosphere in which percentages are no longer relevant. It has become the way of life; the rule rather than the exception. He would see that corruption has destroyed every facet of our national life – our politics, our governments at all levels, our national economy, our judiciary – and retarded our progress in a way difficult to imagine. He would learn that we wage an anti-corruption war, yet the prosecutors of the war shield the corrupt and make them thumb their noses at the rest of us.

And, of course, he would be shocked at the state of our insecurity and see that our country has become perhaps the most insecure functional democracy in Africa. He would wonder why despite the horrors and the trauma of the 30-month civil war, we are still being taken down the path of separatism. He would learn that our inability to properly manage our diversities is at the root of our divisiveness, leading all the tribes to nurse a sense of injury, deprivation and alienation.

But the late prime minister would be charitable enough to say that our politicians have tried and admit that it is not for want of trying that we came to this sorry pass. Nigeria has had a surfeit experiment in nation-building by the khaki politicians and the agbada politicians to end or moderate marginalisation and create a sense of belonging among all the tribes. Why have these experiments systematically unravelled, turned brother against brother and worsened the problems they were intended to solve? It is an important question our first and only prime minister would ponder.

He would be sad to see that the experts on such matters are predicting that our country has failed and is headed for doom and would eventually cease to be if…. He would read this from John Campbell of the Council of Foreign Relations Robert Rotberg of World Peace Foundation: “Nigeria is in big trouble. If a state’s first obligation to those it governs is to provide for their security and maintain a monopoly on the use of violence, then Nigeria has failed even if some other aspects of the state still function. Criminals, separatists and Islamist insurgents increasingly threaten the government’s grip on power, as do rampant corruption, economic malaise, and rising poverty.” A case of government sans governance?

He would learn that in the year 2000, Karl Maier published a book about Nigeria, titled this house has fallen. In it, he would read these harsh views of our country and the prediction that the house built by Lord Lugard is tilting towards a possible collapse: “To most outsiders, the very name Nigeria conjures up images of chaos and confusion, military coups, repression, drug trafficking and business fraud.” And: “Nigerians from all walks of life are openly questioning whether their country should remain as one entity or discard the colonial borders and break apart into several separate states. Ethnic and religious prejudices have found fertile ground in Nigeria.”

He would not be happy to hear from Campbell and Rotberg that “time is running out for Nigeria (and) the country could soon be in even worse shape.”

Would the late prime minister have any fears that this house would fall? Or would he trust our political leaders to rise up to the challenges of proving the doomsayers wrong, clean up the mess, take urgent, honest and committed steps towards rebuilding the nation from the ashes of its avoidable mistakes of both the head and the heart? And we can hail Nigeria again as “our dear native land”? We lose hope at our peril.