|

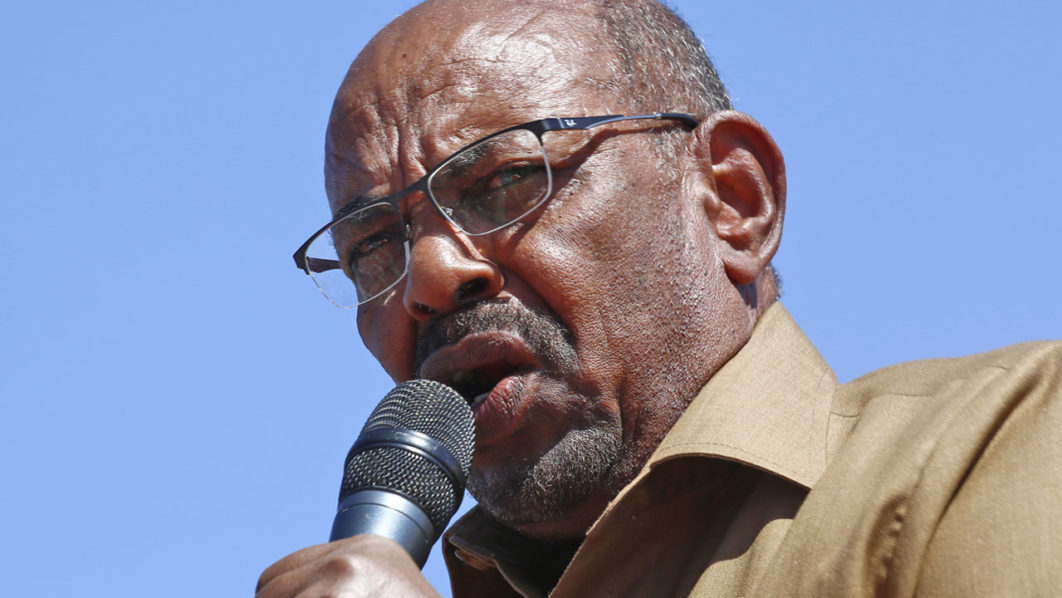

| Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir speaks during a rally with his supporters in the Green Square in the capital Khartoum on January 9, 2019. (Photo by ASHRAF SHAZLY / AFP) |

Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, long wanted on genocide and war crimes charges, has rejected calls to step down in the face of mounting anti-regime demonstrations that have challenged his iron-fisted three-decade rule.

Demonstrators first took to the streets on December 19 to protest against a government decision to triple bread prices, as the African country grapples with an economic crisis.

On Thursday, Sudanese police fired tear gas at protesters marching towards the presidential palace, according to witnesses.

Officials say at least 24 people have been killed and hundreds wounded in unrest that first erupted in towns and villages, before spreading to the capital Khartoum.

Human Rights Watch says at least 40 people have been killed, including children and medical staff.

Over the past month, the demonstrations have also spread to key towns like Port Sudan, Madani, Gadaref and Kassala near the Eritrean border.

Although protests against his regime also took place in September 2013 and January 2018, analysts say the current demonstrations are the biggest challenge since Bashir swept to power in a coup backed by Islamists in 1989.

Indicted by the Hague-based International Criminal Court in 2009 on war crimes charges over a long-running conflict in Darfur, the president has since been re-elected twice in polls boycotted by opposition groups.

In 2010, he was also indicted by the ICC for alleged genocide.

The 75-year-old has proved a political survivor, evading not only the ICC but also a myriad of domestic challenges.

On Monday, dancing and waving a stick in his trademark style, Bashir greeted hundreds of supporters at a rally in Darfur and said that protesters will fail.

“Demonstrations will not change the government,” a defiant Bashir said as supporters, some on camels, chanted “Stay, stay”.

“There’s only one road to power and that is through the ballot box. The Sudanese people will decide in 2020 who will govern them,” said Bashir, who is planning to run again next year.

Career soldier

Despite the ICC indictments, Bashir has regularly visited regional countries and also Russia.

Days before the protests erupted he visited Damascus to meet Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, becoming the first Arab leader to do so since that country’s own conflict began.

At home, Bashir last year hosted talks between neighbouring South Sudan’s leaders, helping to broker a tentative peace deal after five years of intense conflict in the world’s newest country.

South Sudan had gained its independence in 2011, when Bashir surprised his critics by giving his blessing to a secession that saw the south take the bulk of Sudan’s oilfields, some six years after a peace deal ended two decades of north-south conflict.

The president also joined a Saudi-led coalition against Shiite rebels in Yemen, improving ties with the resource-rich Gulf nations, although the policy has been criticised by his opponents at home.

A career soldier, Bashir is well known for his populist touch, insisting on being close to crowds and addressing them in colloquial Sudanese Arabic.

Bashir, who has two wives and no children, was born in 1944 in Hosh Bannaga, north of Khartoum, to a farming family.

He entered the military at a young age, rising through the ranks and joining an elite parachute regiment.

He fought alongside the Egyptian army in the 1973 Arab-Israeli war.

In 1989, then a brigade commander, he led a bloodless coup against the democratically elected government.

Bashir was backed by the National Islamic Front of his then mentor, the late Hassan al-Turabi.

Hosting bin Laden

Under Turabi’s influence he led Sudan towards a more radical brand of Islam, hosting Al-Qaeda founder Osama bin Laden and sending jihadist volunteers to fight in the country’s civil war with the south Sudanese.

In 1993, Washington put Sudan on its list of “state sponsors of terrorism” and four years later slapped Khartoum with a trade embargo — only lifted in 2017 — over charges that included human rights abuses.

Bashir sought to end Sudan’s isolation in 1999, ousting Turabi from his inner circle.

But when insurgents launched a rebellion in Darfur in 2003, his government’s decision to unleash the armed forces and allied militia saw him face further international criticism.

More than 300,000 people have been killed in the Darfur conflict, the UN says, and more than two million displaced.

Since 2011, Bashir has also faced insurgencies in South Kordofan and Blue Nile states, launched by the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-North.

Although he has weathered multiple challenges in his three-decade rule, analysts question whether he will survive the latest bout of protests.

“The demonstrations have weakened his position,” said Khalid Tijani, editor of economic weekly Elaff.

“President Bashir constitutionalget consitutional amendments to permit him to run for the presidency again in 2020, but he will now have to reconsider that,” he said.

Demonstrators first took to the streets on December 19 to protest against a government decision to triple bread prices, as the African country grapples with an economic crisis.

On Thursday, Sudanese police fired tear gas at protesters marching towards the presidential palace, according to witnesses.

Officials say at least 24 people have been killed and hundreds wounded in unrest that first erupted in towns and villages, before spreading to the capital Khartoum.

Human Rights Watch says at least 40 people have been killed, including children and medical staff.

Over the past month, the demonstrations have also spread to key towns like Port Sudan, Madani, Gadaref and Kassala near the Eritrean border.

Although protests against his regime also took place in September 2013 and January 2018, analysts say the current demonstrations are the biggest challenge since Bashir swept to power in a coup backed by Islamists in 1989.

Indicted by the Hague-based International Criminal Court in 2009 on war crimes charges over a long-running conflict in Darfur, the president has since been re-elected twice in polls boycotted by opposition groups.

In 2010, he was also indicted by the ICC for alleged genocide.

The 75-year-old has proved a political survivor, evading not only the ICC but also a myriad of domestic challenges.

On Monday, dancing and waving a stick in his trademark style, Bashir greeted hundreds of supporters at a rally in Darfur and said that protesters will fail.

“Demonstrations will not change the government,” a defiant Bashir said as supporters, some on camels, chanted “Stay, stay”.

“There’s only one road to power and that is through the ballot box. The Sudanese people will decide in 2020 who will govern them,” said Bashir, who is planning to run again next year.

Career soldier

Despite the ICC indictments, Bashir has regularly visited regional countries and also Russia.

Days before the protests erupted he visited Damascus to meet Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, becoming the first Arab leader to do so since that country’s own conflict began.

At home, Bashir last year hosted talks between neighbouring South Sudan’s leaders, helping to broker a tentative peace deal after five years of intense conflict in the world’s newest country.

South Sudan had gained its independence in 2011, when Bashir surprised his critics by giving his blessing to a secession that saw the south take the bulk of Sudan’s oilfields, some six years after a peace deal ended two decades of north-south conflict.

The president also joined a Saudi-led coalition against Shiite rebels in Yemen, improving ties with the resource-rich Gulf nations, although the policy has been criticised by his opponents at home.

A career soldier, Bashir is well known for his populist touch, insisting on being close to crowds and addressing them in colloquial Sudanese Arabic.

Bashir, who has two wives and no children, was born in 1944 in Hosh Bannaga, north of Khartoum, to a farming family.

He entered the military at a young age, rising through the ranks and joining an elite parachute regiment.

He fought alongside the Egyptian army in the 1973 Arab-Israeli war.

In 1989, then a brigade commander, he led a bloodless coup against the democratically elected government.

Bashir was backed by the National Islamic Front of his then mentor, the late Hassan al-Turabi.

Hosting bin Laden

Under Turabi’s influence he led Sudan towards a more radical brand of Islam, hosting Al-Qaeda founder Osama bin Laden and sending jihadist volunteers to fight in the country’s civil war with the south Sudanese.

In 1993, Washington put Sudan on its list of “state sponsors of terrorism” and four years later slapped Khartoum with a trade embargo — only lifted in 2017 — over charges that included human rights abuses.

Bashir sought to end Sudan’s isolation in 1999, ousting Turabi from his inner circle.

But when insurgents launched a rebellion in Darfur in 2003, his government’s decision to unleash the armed forces and allied militia saw him face further international criticism.

More than 300,000 people have been killed in the Darfur conflict, the UN says, and more than two million displaced.

Since 2011, Bashir has also faced insurgencies in South Kordofan and Blue Nile states, launched by the Sudan People’s Liberation Army-North.

Although he has weathered multiple challenges in his three-decade rule, analysts question whether he will survive the latest bout of protests.

“The demonstrations have weakened his position,” said Khalid Tijani, editor of economic weekly Elaff.

“President Bashir constitutionalget consitutional amendments to permit him to run for the presidency again in 2020, but he will now have to reconsider that,” he said.

AFP

In this article: